On David Foster Wallace and the Terrible Sport of Branding Yourself

I swore on my life I would walk away from social media without a blink. The blah-blah of the Internet has been unusually annoying, and I just don’t feel like being around it anymore. It has ruined the best minds of my generation. It has ruined mine, too.

I nearly succeeded at walking away from it. I suspended my social media accounts and lasted three weeks without even peeking at Reddit or the New York Times or whatever other powdery drugs are peddled into my palm every day.

But then a literary agent, whom we’ll call Miss Floofy, rejected my picture book series like a champ and told me that anyone who has any hope of getting published neeeeeeds to be on Instagram. It was a non-starter, she said. Agents and publishers and readers want to see your inner world.

It all felt very 2010, if I’m honest, because as far as I can tell, the Internet is totally broken for anyone with an old fashioned thing called “a soul.” Besides, most writers lead rather mundane inner lives (photos of tea and cats can only go so far). If I could make the rules of publishing, which I can’t, I would declare that writers abandon the sport of marketing altogether and leave it to the billions and billions of cheery non-writers in the world.

And so, here we are. I’m back on Instagram and I’m promoting “my brand.” I want to vomit.

All this brings me to David Foster Wallace who, in my opinion, is the greatest writer of the 90s and possibly the greatest writer of the 20th century. I say this having never stomached the full Infinite Jest (though it recently rose to top spot on my 2025 To Do list). Instead I speak of DFW’s transcendent essays, the collections of which sit substacked on my nightstand, next to a puppy-eyed Bible. Sometimes I swear I hear God’s voice coming out of them and saying, “See Kate, I gave the world a second son.”

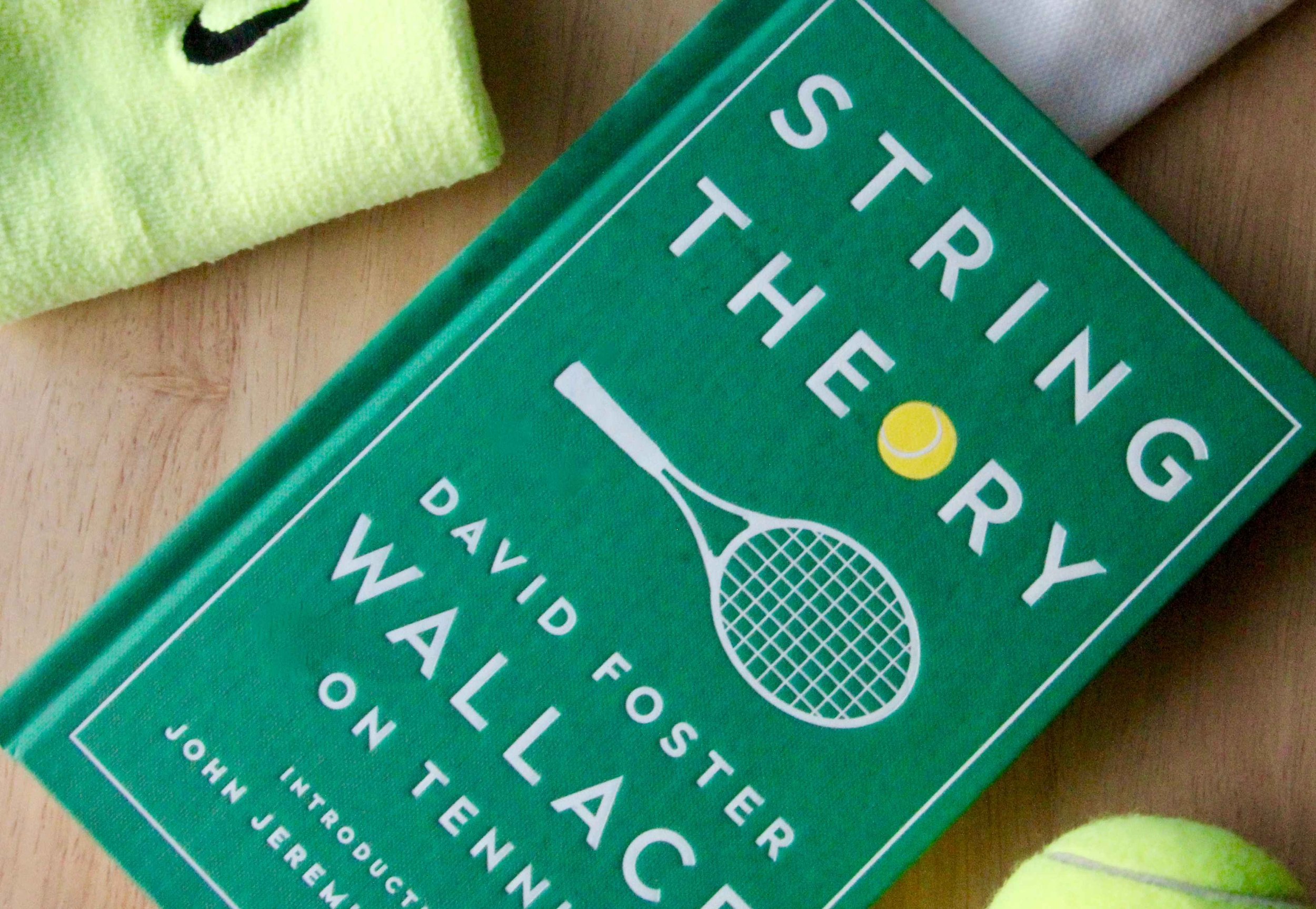

Unlike God’s first son, most people have never heard of DFW. That is fine. Most people have never heard of most people. He wrote about a lot of things, but he especially loved to write about tennis. He was an avid player and enraptured fan, and his tennis essays were collected in a gorgeous little book called String Theory. (This book is the best gift you can ever get a tennis fan, unless your tennis fan doesn’t like to read, in which case, I don’t know, get him custom wristbands). I read a little bit of String Theory every week, return to it a little later, re-read it, and so on. I’ve done this for years, even though it’s a tiny thing, much tinier than a Bible, which I’ve barely thumbed.

This week I read a little of String Theory out loud to Christoph—my tennis fanatic of a husband. (I myself play a little tennis. I’m terrible at it. But it is a part of my life now because Christoph is a part of my life now.)

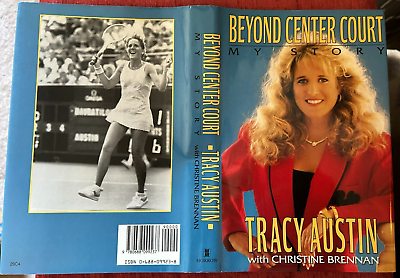

I read him DFW’s brilliant and hilariously scathing critique of Tracy Austin’s memoir, Beyond Center Court. Tracy Austin is a player whose name is all but unrecognizable to most people today, but in 1980—at age FOURTEEN—she became world number 1. This was, and is, one of the most spectacular sports feats of all time. The tennis world quaked apart and showed a lode that nobody knew could exist.

When given a chance to describe her career to readers, Tracy Austin sums it up like this:

“It was tough.”

and:

“I won easily.”

Here’s an athlete with one of the most interesting stories of all time—and this is how it is told?

Poor DFW writhes at this. And writhes at this. And in bubonic agony, he takes laugh-out-loud shots at Austin’s inability to articulate herself.

But he goes on to argue that it’s perhaps all very simple: professional athletes are pretty much incapable of articulating their experience to the rest of us. Athletes (the very good ones) are dumb as rocks when it comes to their sport (but possibly not elsewhere in their lives) and the rock-substance-between-the-ears is exactly what makes them so utterly brilliant. In other words, they need the cold, blank slate to achieve their earth-defying feats on the court (or other surfaces). He writes:

It may well be that we spectators, who are not divinely gifted as athletes, are the only ones able truly to see, articulate, and animate the experience of the gift we are denied. And that those who receive and act out the gift of athletic genius must, perforce, be blind and dumb about it—and not because blindness and dumbness are the price of the gift, but because they are its essence.

DFW is an aesthete with a sesquipedalian vocabulary. You picture his sort in high school and you wonder just how many lockers braced for impact each time he walked by. But then you realize that actually, probably, he never once found himself on the fist-side of a bully because there is something superhumanly kind about this guy. Even when he is eviscerating a writer’s work, he is doing it not to mock them but to show the world just how much of an unrecognized genius this person is, a genius whose talent transcends the common bits of human language that the rest of us “literary types” are forced to dink around with. Somehow he pulls off his whole argument without ever sounding like he is picking a fight with the jocks, but rather like he is begging for a chance to stand at the dimmest boundary of their glow.

Ahh, so at last we loop back to my point. It’s brief:

The essay on Tracy Austin got me wondering whether being a writer and trying to market your own brand is anything at all like being a writer and trying to be a professional athlete. The two sides of the soul use such different fuel that they risk burning down the whole lab—rendering both “The Art” and “The Marketability of the Art” basically cindered. We’re all lame now, our whole mash of creativity and branding just dumb, and if Miss Floofy is right, there is no way out of it for a budding creator like myself. I don’t have a cat, and I don’t have a typewriter, so here—have my inner gibberish about God’s second son.